A guest post by Fareeha Molvi, a Pakistani-American freelance journalist based in Los Angeles. Unless otherwise noted all images are from Ms. Marvel’s official tumblr page.

Earlier this month, comic book publisher Marvel released part one of the new Ms. Marvel series, which follows the story of teenage Pakistani-American Muslim Kamala Khan. The comic–which unfolds over five monthly installments–has garnered international publicity for months since its publisher announced its release last fall. The revamp of the Ms. Marvel series, which originally began in the ‘70s, is part of an initiative by the publisher to appeal to a growing female fanbase by introducing more female characters and female-centric storylines.

Of course for the Pakistani-American diaspora, much of the surrounding buzz has more to do with the title character’s heritage and religion at a time when representation of Pakistani-American characters in American media and art is still sorely limited. Unlike Indian-Americans, whose ethnic identities are part of the backstories of major characters on primetime shows like “The Mindy Project” and “New Girl,” media portrayals of Pakistani-American Muslims consist of one-dimensional or tokenized roles as the terrorists in “24” or the doctor in a random episode of “Friends.” That Marvel, the force responsible for blockbuster franchises like X-Men, Iron Man, and Spiderman among others, has chosen a Pakistani-American Muslim woman to headline this series is a significant leap. In fact, since the comic’s release, a flurry of articles have published voicing overwhelming support for the book and its creators.

But the comic book world is no stranger to topical discussions of race, religion and representation. Stan Lee, co-creator of Marvel’s centerpiece franchise X-Men, has said that the series (which centers on a cast of ethnically diverse mutants and their quest for acceptance within American society) is an allegory to the African-American struggle for equality in the 1960s. “The whole underlying principal of the X-Men was to try to be an anti-bigotry story to show there’s good in every person,” Lee said.

If comics are meant to capture the zeitgeist of the time, it isn’t difficult to see why the new Ms. Marvel, who was originally conceived as a self-assured leggy blonde pilot during the height of the 1970’s Feminist movement, is now a child of Pakistani Muslim immigrants attempting to navigate a hyphenated identity in the aftermath of 9/11. Seeing as this description perfectly encapsulates my life, as well as many others in the diaspora, I anxiously anticipated the release of the first character I might be able to relate to on every level.

While Kamala Khan isn’t technically the first Muslim hero to appear in comics, she does seem to be the most relatable. Dust, a niqab-clad Afghan woman who can transform into a cloud of sand, appeared as a side character in Marvel’s X-Men in 2002. Rival publisher DC Comics has Nightrunner, a French-Algerian Muslim man living in Paris who partners with Batman. In 2011 they introduced Simon Baz, a Lebanese-American Muslim from Dearborn, Michigan who becomes Green Lantern after being suspected of terrorist activity by the FBI.

But where these characters experience extraordinary circumstances, Kamala is just an average second-generation teen living in the suburbs and trying to fit in. Dust, by contrast, is captured by slave-traders in Afghanistan and then escapes with the X-Men to India. Baz is a street-racer who steals cars after getting laid off. The challenges in Kamala’s life include dietary restrictions and celebrating the “weird holidays.” These are the same obstacles that made me, and many other Muslims growing up in America, feel otherized. In this ordinariness lies her relatability.

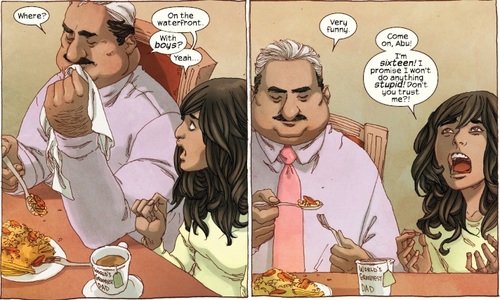

Sana Amanat, the comic’s editor, has said the concept of Kamala came about as result of telling her colleague about a peculiar anecdote related to her growing up as a Pakistani-American Muslim. But she and her team did not want to tokenize her character by drawing her as a one-dimensional, “model Muslim.” The comic’s writer, G. Willow Wilson said she worked with Amanat to create a fully-realized personality that would appeal to a broad audience.The result is a gaming geek (to resonate with comic book readers) who you might find at a thrift store shopping for hipster clothes. Of course, her struggles with parental authority and a desire to mesh with the popular crowd are familiar to anyone who has graduated high school. Kamala also just happens to be Muslim and the daughter of Pakistani immigrants. In presenting a character like this, without tokenizing or exotifying her, the creators have introduced a vision of middle-class, second-generation, Muslim-American normalcy that has been a part of the American demographic for at least two decades but has not been explored in media until now.

Many have drawn parallels between 16-year-old Kamala and real-life Pakistani superteen Malala Yousufzai, who gained international attention after the Taliban attempted to assassinate her for her education activism in rural Pakistan. But, while I admire and applaud Yousufzai’s work, I cannot relate to her. Maybe it’s a function of growing up in the diaspora but I have the privilege of being disconnected from the immense struggles — drones, political instability, internal violence — that Yousufzai and others living in Pakistan have to face daily.

However, Kamala’s challenges, which probably pale in comparison to Yousufzai’s, are the ones I identify with. She is negotiating multiple identities –Muslim, Pakistani, American–and grappling with how they can coexist peacefully within herself, if at all. When Kamala’s father refuses to allow her to go to a party where both boys and girls will be present, the internal dialogue that goes through her mind could have been lifted directly from my high school brain. “I always do what they want me to do,” she muses, “aren’t I allowed to do anything my way?”

Depictions of angst-ridden adolescence are not new to American media but there is a difference when you come of age with immigrant parents. Emigration to America, for many Pakistanis of my parents’ generation, was a chance to find better opportunities for themselves and their children. Rebelling against their hopes and expectations is underlined with the guilt of throwing away the immense sacrifices they endured to establish a life for us in a foreign place. When Kamala decides to stifle these concerns and sneaks out to the party anyway, she is still considered an outsider, as evidenced by her classmate who expresses mock-concern that she is out at night and not “locked up.” So, the upshot is, as a child of immigrants, you are never going to fit in completely in either world, neither the one of your parents nor of your peers.

During a hallucination, Kamala meets her idols, Captain America and the original Ms. Marvel, Carol Danvers. In a particularly poignant moment, Captain America rebukes Kamala for her decision to go to the party by asking, “You thought that if you disobeyed your parents–your culture, your religion–your classmates would accept you.” She then realizes that by undermining her parents’ authority, she gave permission to her classmates to belittle her family and upbringing. “Like Kamala’s finally seen the light and kicked the dumb inferior brown people and their rules to the curb,” she says. This scene perfectly encapsulates the unique tension many second-generation children feel when balancing the desire to protect the values and beliefs of their heritage with attempting to integrate into mainstream society.

Kamala voices this sentiment when she expresses her desire to want to be like the white, blonde Danvers who she thinks is “beautiful and awesome and butt-kicking and less complicated.” For Kamala, a white facade seems like the answer to her adolescent problems.

But even though Danvers warns her things won’t turn out the way she expects, Kamala gets her wish and the comic ends with her reborn in the form of a blonde bombshell. The scene is admittedly ridiculous, but the fact that the authors chose it as a cliffhanger strikes at a deeper layer of the second-generation experience: the thought that life would be easier without cultural baggage. From my research of the comic, I know that Kamala’s form is only temporary, because her power is shape-shifting, but the inclusion of this scene represents an important part of the quest to “normalcy” familiar to many second-generation readers, regardless of cultural or religious background.

Some might argue that most comic book heroes are misfits, so why is Kamala special? Peter Parker for instance, before becoming Spiderman, is a science-whiz and loner who doesn’t fit in with the popular crowd at his high school. But not fitting in as a result of your personal interests and personality is completely different from feeling otherized as a function of your historical, cultural and religious roots. There is a nuance to Kamala’s otherness that plays out authentically because the comic pulls from the experiences of its editor, Amanat. That her experience was compelling enough to spawn an entire series that centers around someone who looks and thinks like me validates my experience and that of many in the Pakistani-American Muslim diaspora.

However, the comic’s creators have made it clear that they do not wish for Kamala’s heritage or religion to be the focal point of the comic. Wilson has said they wanted it to be about “about the universal experience of all American teenagers, feeling kind of isolated and finding what they are [but] through the lens of being a Muslim-American.” Kamala’s experience of awkward adolescence is relatable to a broad audience, no doubt, but she is also different as a result of her upbringing — which is the reality of claiming intersectional identities. You cannot parse one from the other, making its representation in media and art a delicately complex balancing act. Perhaps this is why, for so long, this narrative has been ignored or labeled as a fringe experience irrelevant to mainstream America. With the release of Ms. Marvel, however, a medium has risen to the challenge and deemed our experience worthy of inclusion in the greater American narrative. And that is why Kamala Khan matters.